Where We Came From

Where We Came From: A Brief History of the Disability Rights

Movement and Disability Discrimination

Prepared by Disability Rights Center staff, 2004-2010

Special thanks to the Bancroft Library at the University of California Berkeley

THE DISABILITY RIGHTS MOVEMENT

The disability rights movement came to fruition in the 1960s after significant groundwork was laid by numerous individuals from around the country. All of those people in all of those places were reacting to one common issue – people with disabilities have the right to experience life in the same manner, and to the same degree as Americans without disabilities. Building on the growing civil rights movement, people with disabilities began demanding access to education, services and lifestyles that others enjoyed. The “formalization” of the disability rights movement was found in the development of the Independent Living Movement beginning in Berkeley California in 1970 with the establishment of the Center for Independent Living.

A Chronology of the Disability Rights Movement

It’s difficult to pinpoint the time, place and people that initiated the disability rights movement. This is just one perspective on the important events, people and places that would bear the infant to become known as the disability rights movement. It is important to note that the disability rights movement did not begin in a vacuum, it was one small part of the larger civil rights movement that was happening throughout America. Although the “movement” is not recognized as an organized civil rights struggle before 1962, there were several important events that created the fertile ground from which the movement would spring up. The following are just a few of the most important events.

1920 - The Fess-Smith Civilian Vocational Rehabilitation Act is passed, creating a vocational rehabilitation program for civilians with disabilities. This was very much a response to the number of disabled Vets returning from WWI.

1935 - Congress passes and President Franklin D. Roosevelt signs the Social Security Act, establishing federal old-age benefits and grants to the states for assistance to blind individuals and disabled children. The act also extends the already existing vocational rehabilitation programs established by earlier legislation.

The League of the Physically Handicapped is formed in New York City to protest discrimination against people with disabilities by federal relief programs. The group organizes sit-ins, picket lines, and demonstrations, and it travels to Washington, D.C., to protest and meet with officials of the Roosevelt administration.

1938 - The American Federation of the Physically Handicapped is founded by Paul Strachan as the nation’s first cross-disability, national political organization. It pushes for an end to job discrimination and lobbies for passage of legislation calling for a National Employ the Physically Handicapped Week, among other initiatives.

1946 - The first meeting of the Presidents Committee on National Employ the Physically Handicapped Week is held in Washington, D.C. Its publicity campaigns, coordinated by state and local committees, emphasize the competence of people with disabilities and use movie trailers, billboards, and radio and television ads to convince the public that its “good business to hire the handicapped.”

1950 - The Social Security Amendments of 1950 establish a federal-state program to aid the permanently and totally disabled (APTD). This is a limited prototype for later federal disability assistance programs such as Social Security Disability Insurance.

The Association for Retarded Children of the United States (later renamed the Association for Retarded Citizens and then The ARC) is founded in Minneapolis by representatives of various state association of parents of mentally retarded children.

Mary Switzer is appointed Director of the federal Office of Vocational Rehabilitation.

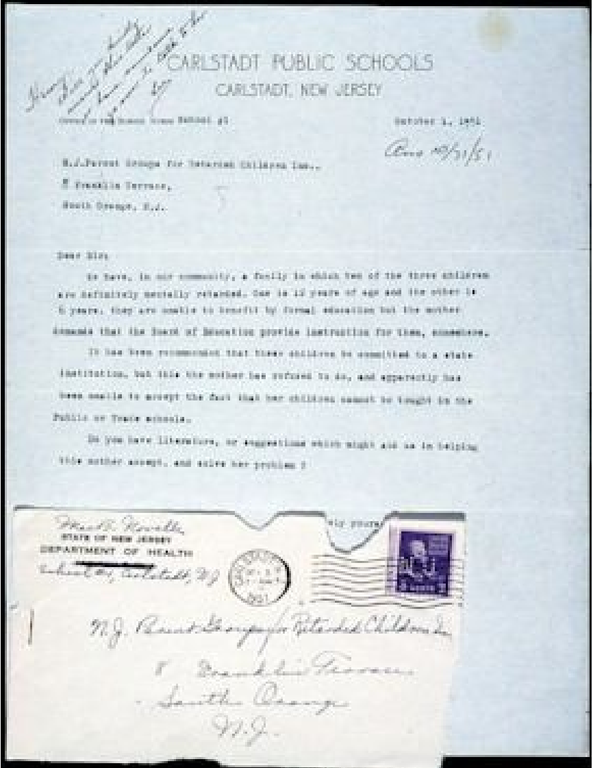

1951 - This is a 1951 letter from someone in the nurse’s office at Carlstadt, New Jersey Public School #1 and sent to the New Jersey Parent Groups for Retarded Children. The cancelled envelope from the letter is stapled to the bottom of the letter.

The Letter reads:

"Dear Sir: We have, in our community, a family in which two of the three children are definitely mentally retarded. One is 12 years of age and the other is 6 years. They are unable to benefit by formal education but the mother demands that the Board of Education provide instruction for them.

It has been recommended that these children be committed to a state institution, but this the mother has refused to do, and apparently has been unable to accept the fact that her children cannot be tought [misspelled in the original] in the Public or Trade schools.

Do you have any literature, or suggestions which might aid us in helping this mother accept, and resolve her problem?"

1952 - The President’s Committee on National Employ the Physically Handicapped Week becomes the Presidents’ Committee on Employment of the Physically Handicapped, a permanent organization reporting to the President and Congress.

1954 - The U.S. Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, rules that separate schools for black and white children are inherently unequal and unconstitutional. This pivotal decision becomes a catalyst for the African-American civil rights movement, which in turn becomes a major inspiration to the disability rights movement.

Congress passes the Vocational Rehabilitation Amendments, authorizing federal grants to expand programs available to people with physical disabilities.

This is a black and white photograph of about twenty disabled veterans in wheelchairs. The men are waiting in a line on the sidewalk along the wall of an office building. The wall looks like the façade of a government building, with smooth grey stone and tall, barred windows. The men wear clothes of the 1940s and 1950s: wide lapels, white socks and dark shoes, cardigan sweaters. One man smokes a pipe and is wearing a suit with a wide striped tie and Argyll socks. The men hold signs that say: "How Dare They?"; "Keep Faith in Disabled Vets"; "How About the East Orange VA Hospital"; "We Did Our Share, Treat Us Right": "PVA"; "Don't Break Promises".

Mary Switzer, Director of the Office of Vocational Rehabilitation, uses this authority to fund more than 100 university based rehabilitation related programs.

1956 - Congress passes the Social Security Amendments of 1956, which creates a Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) program for disabled workers aged 50 to 64.

1961 - President Kennedy appoints a special President’s Panel on Mental Retardation, to investigate the status of people with mental and develop programs and reforms for its improvement.

The American National Standard Institute, Inc. (ANSI) publishes American Standard Specifications for Making Buildings Accessible to, and Usable by, the Physically Handicapped. This landmark document becomes the basis for all subsequent architectural access codes.

1962 - The President’s Committee on Employment of the Physically Handicapped is renamed the President’s Committee on Employment of the Handicapped, reflecting its increased interest in employment issues affecting people with cognitive disabilities and mental illness.

Edward V. Roberts, generally accepted as the father of the modern Disability Rights Movement becomes the first severely disabled student at the University of California at Berkeley.

1963 - President Kennedy, in an address to Congress, calls for a reduction, “over a number of years and by hundreds of thousands, (in the number) of persons confined” to residential institutions, and he asks that methods be found “to retain in and return to the community the mentally ill and mentally retarded, and there to restore and revitalize their lives through better health programs and strengthened educational and rehabilitation services.” Though not labeled such at the time, this is a call for deinstitutionalization and increased community services.

John Hessler joins Ed Roberts at the University of California at Berkeley, other disabled students follow. Together they form the Rolling Quads to advocate for greater access on campus and in the surrounding community. The Rolling Quads use the civil rights movement happening in Berkeley as the structure and model to develop and begin the modern disability rights movement. At that time they, along with many others had been living in a hospital on the Campus. Today, the old hospital that housed the disabled students program is the location of the UC Berkeley School of Business.

1964 - The Civil Rights Act is passed, outlawing discrimination on the basis of race in public accommodations and employment, as well as in federally assisted programs. It will become a model for subsequent disability rights legislation.

Robert H. Weitbrecht invents the “acoustic coupler,” forerunner of the telephone modem, enabling teletypewriter messages to be sent via standard telephone lines. This invention makes possible the widespread use of teletypewriters for the deaf (TDD’s also called TTY’s), offering deaf and hard-of-hearing people access to the telephone system.

1965 - Medicare and Medicaid are established through passage of the Social Security Amendments of 1965. These programs provide federally subsidized health care to disabled and elderly Americans covered by the Social Security program. The amendments also change the definition of disability under the Social Security Disability Insurance program, from “of long continued and indefinite duration” to “expected to last for not less than 12 months.”

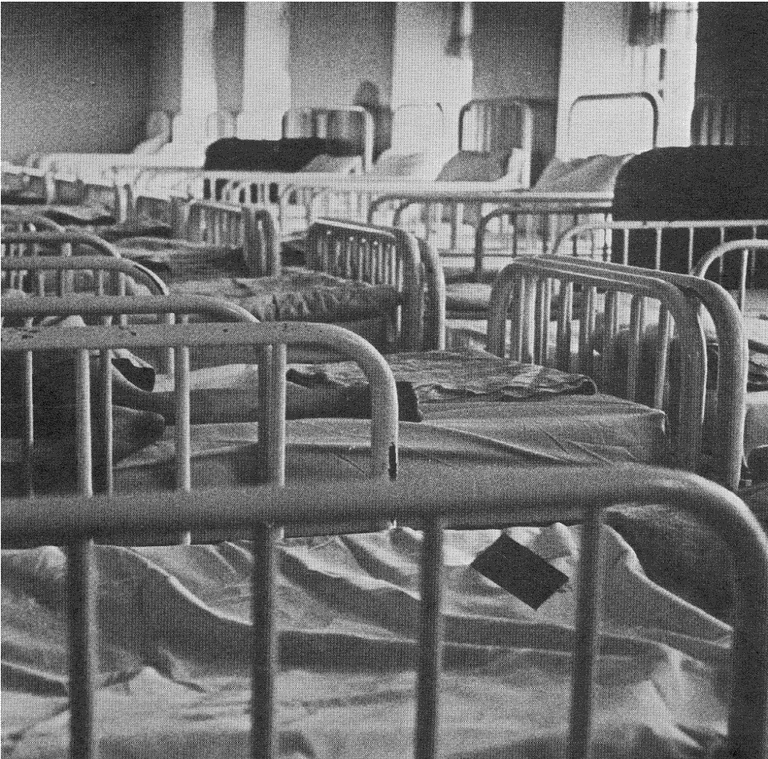

Christmas in Purgatory by Burton Blatt and Fred Kaplan, is published, documenting the appalling conditions at state institutions for people with developmental disabilities. This photographic essay about the state of institutions in America is still available today. Many of the photos used in this presentation are from Christmas in Purgatory.

1968 - The Architectural Barriers Act is passed, mandating that federally constructed buildings and facilities be accessible to people with physical disabilities. This act is generally considered to be the first ever-federal disability rights legislation.

1969 - Niels Erk Bank-Mikkelsen from Denmark and Bengt Nirje from Sweden introduce the concept of normalization to an American audience at a conference sponsored by the President’s Committee on Mental Retardation, helping to provide the conceptual framework for deinstitutionalization. Their remarks, and those of others, are published in Changing Patterns in Services for the Mentally Retarded.

1970 - The Physically Disabled Students Program (PDSP) is founded by Ed Roberts, John Hessler, Hale Zukas, and others at the University of California at Berkeley. With its provisions for community living, political advocacy, and personal assistance services, it becomes the nucleus for the first Center for Independent Living, founded two years later. In a communication to Gini Laurie in 1970, Ed stated the following,

“I have begun a consultation business for anyone needing help with problems with cripples. I've consulted with Health Education in Washington, DC, about programs for cripples in higher education, help secured $80,000 grant for UC Berkeley program run by cripples for the education of cripples. I brought John Hessler in as director. He is doing a magnificent job. Would you like to hear more? I believe no other consulting firm like this in the country.”

He continued,

I'm tired of well meaning noncripples with their stereotypes of what I can and cannot do directing my life and my future. I want cripples to direct their own programs and to be able to train other cripples to direct new programs. This is the start of something big -- cripple power.” -Ed

Ed Roberts was starting a self help movement that would radicalize how people with disabilities perceived themselves. He did it for himself and then began laying the groundwork for the rest of us. Independence and rehabilitation have not been the same since, and will never return to the archaic notions which perceived people with disabilities as passive recipients of charity, unable to self direct their lives.

Ed Roberts & John Hessler

Ed Roberts & Judy Heumann

Disabled in Action is founded in New York City by Judith Heumann, after her successful employment discrimination suit against the city’s public school system. With chapters in several other cities, it organizes demonstrations and files litigation on behalf of disability rights.

1971 - The National Center for Law and the Handicapped is founded at the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana, becoming the first legal advocacy center for people with disabilities in the United States.

The U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Alabama hands down its first decision in Wyatt v. Stickney, ruling that people in residential state schools and institutions have a constitutional right “to receive such individual treatment as (would) give them a realistic opportunity to be cured or to improve his or her mental condition.” Disabled people can no longer simply be locked away in “custodial institutions” without treatment or education. This decision is a crucial victory in the struggle for deinstitutionalization.

1972 - The U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, in Mills v. Board of Education, rules that the District of Columbia cannot exclude disabled children from the public schools. Similarly, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, in PARC v. Pennsylvania, strikes down various state laws used to exclude disabled children from the public schools. These decisions will be cited by advocates during the public hearings leading to passage of the Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975. PARC in particular sparks numerous other right-to-education lawsuits and inspires advocates to look to the courts for the expansion of disability rights.

The Center for Independent Living (CIL) is founded in Berkeley, California. Generally recognized as the world’s first independent living center, the CIL sparks the worldwide independent living movement.

Passage of the Social Security Amendments of 1972 creates the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program. The law relieves families of the financial responsibility of caring for their adult disabled children. It consolidates existing federal programs for people who are disabled but not eligible for Social Security Disability Insurance.

1973 - The Network Against Psychiatric Assault is organized in San Francisco. The parents of residents at the Willow Brook State School in Staten Island, New York file suit (New York ARC v. Rockefeller) to end the appalling conditions at that institution. A television broadcast from the facility outrages the general public, which sees the inhumane treatment endured by people with developmental disabilities. This press exposure, together with the lawsuit and other advocacy, eventually moves thousands of people from the institution into community-based living arrangements.

Demonstrations are held by disabled activists in Washington, D.C., to protest the veto of what will become the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 by President Richard M. Nixon. Among those organizing demonstrations in Washington and elsewhere are Disabled in Action, Paralyzed Veterans of America, the National Paraplegia Foundation, and other groups.

1974 - Halderman v. Pennhurst is filed in Pennsylvania on behalf of the residents of the Pennhurst State School & Hospital. The case, highlighting the horrific conditions at state “schools” for people with mental retardation, becomes an important precedent in the battle for deinstitutionalization, establishing a right to community services for people with developmental disabilities.

The first convention of People First is held in Salem, Oregon. People First become the largest U.S. organization composed of and led by people with cognitive disabilities.

1975 - Congress passes the Developmentally Disabled Assistance and Bill of Rights Act, providing federal funds to programs serving people with developmental disabilities and outlining a series of rights for those who are institutionalized. The lack of an enforcement mechanism within the bill and subsequent court decisions, will, however, render this portion of the act virtually useless to disability rights advocates.

The Education for All Handicapped Children Act (Pub. Law 94-142) is passed, establishing the right of children with disabilities to a public school education in an integrated environment. The act is a cornerstone of federal disability rights legislation. In the next two decades, millions of disabled children will be educated under its provisions, radically changing the lives of people in the disability community.

The Atlantis Community is founded in Denver as a group-housing program for severely disabled adults who, until that time, had been forced to live in nursing homes. Atlantis will later for the American Disabled for Accessible Public Transportation (ADAPT), an organization focused on public demonstrations and civil disobedience to create the political will to change.

Edward Roberts becomes the Director of the California Department of Rehabilitation. He moves to establish nine independent living centers across that state, based on the model of the original Center for Independent Living in Berkeley. The success of these centers demonstrates that independent living can be replicated and eventually results in the founding of hundreds of independent living centers all over the world.

This is a faded color photograph showing a flat suburban neighborhood street. It is quiet and deserted. There is no sidewalk but a slightly worn grassy footpath edges the side of the street. A flat area of close cut grass extends out from the curb along the street. There is a street light on a high pole. In the background rises a two-story brick building and two white houses with big trees in the front yards. TV aerials are visible on rooftops in the distance. A car is just rounding the corner at the far end of the street and headed this way, perhaps into a parking lot or down another street. There is a white metal sign with black letters placed at the curb that reads: "No Wheel Chairs Beyond this Point."

1977 - Disability rights activists in ten cities stage demonstrations and occupations of the offices of the federal department of Health Education and Welfare (HEW) to force the Carter Administration to issue regulations implementation Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. The demonstrations galvanize the disability community nationwide, particularly the San Francisco action, which lasts nearly a month. On 28 April, HEW Secretary Joseph Califano finally signs the regulations.

The U.S. Court of appeals for the Seventh Circuit, in Lloyd V. Regional Transportation authority, rules that individuals have a right to sue under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and that public transit authorities must provide accessible service. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, in Snowden v. Birmingham Jefferson County Transit Authority, undermines this decision by ruling that authorities need provide access only to “handicapped persons other than those confined to wheelchairs.”

1978 - Disability rights activism in Denver stage a sit-in demonstration, blocking several Denver Regional Transit Authority buses, to protest the complete inaccessibility of that city’s mass transit system. The demonstration is organized by the Atlantis Community and is the first action in what will be a yearlong civil disobedience campaign to force the Denver Transit Authority to purchase wheelchair lift-equipped buses.

Title VII of the Rehabilitation Act Amendments of 1978 establishes the first federal funding for independent living and creates the National Council of the Handicapped under the U.S. Department of Education.

1979 - The U.S. Supreme Court, in Southeastern Community College v. Davis, rules that, under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, programs receiving federal funds must make “reasonable modifications” to enable the participation of otherwise qualified disabled individuals. This decision is the Court’s first ruling on Section 504, and it establishes reasonable modification as an important principle in disability rights law.

The National Alliance for the Mentally Ill is founded in Madison, Wisconsin, by parents of persons with mental illness.

1980 - Congress passes the Social Security Amendments, with Section 1619 designed to address work disincentives within the Social Security Disability Insurance and Supplemental Security Income programs. Other provisions mandate a review of Social Security recipients, leading to the termination of benefits of hundreds of thousands of people with disabilities.

1981 - Congress passes the Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act, authorizing the U.S. Justice Department to file civil suits on behalf of residents of institutions whose rights are being violated.

In an editorial in the New York Timer, Evan Kemp Jr. attacks the Jerry Lewis National Muscular Dystrophy Association Telethon, writing that “the very human desire for cures can never justify a television show that reinforces a stigma against disabled people.”

1981-1983 - The newly elected Reagan Administration threatens to amend or revoke regulations implementing Section 504 1983 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975. Disability rights advocates, led by Patrisha Wright at the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund (DREDF) and Evan Kemp, Jr. at the Disability Rights Center, respond with an intensive lobbying effort and a grassroots campaign that generates more than 40,000 cards and letters. After three years, the Reagan Administration abandons its attempts to revoke or amend the regulations.

1981-1984 - The Reagan Administration terminates the Social Security benefits of hundreds of thousands of disabled recipients. Advocates charge that these terminations are an effort to reduce the federal budget and often do not reflect any improvement in the condition of those being terminated. A variety of groups, including the Alliance of Social Security Disability Recipients and the Ad Hoc Committee on Social Security Disability, spring up to fight these terminations. Several disabled people, in despair over the loss of their benefits, commit suicide.

The parents of “Baby Doe” in Bloomington, Indiana, are advised by their doctors to deny a surgical procedure to unblock their newborn’s esophagus, because the baby has Down Syndrome. Although disability rights activists try to intervene, Baby Doe starves to death before legal action can be taken. The case prompts the Reagan Administration to issue regulations calling for the creation of “Baby Doe squads” to safeguard the civil rights of disabled newborns.

1983 - American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit (ADAPT) is organized at the Atlantis Community Headquarters in Denver, Colorado. For the next seven years ADAPT conducts a civil disobedience campaign against the American Public Transit Association (APTA) and various local public transit authorities to protest the lack of accessible public transportation.

1984 - The Baby Jane Doe case, like the 1982 Bloomington Baby Doe case, involves an infant being denied needed medical care because of her disability. The case results in litigation argued before the U.S. Supreme Court in Bowen v. American Hospital Association, and in passage of the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act Amendments of 1984.

The U.S. Supreme Court rules, in Irving Independent School District v. Tatro, that school districts are required under the Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975 to provide intermittent catheterization, performed by the school nurse or a nurse’s aide, as a “related service” to a disabled student. School districts can no longer refuse to educate a disabled child because they might need such a service.

Congress passes the Social Security Disability Reform Act in response to the complaints of hundreds of thousands of people whose Social Security disability benefits have been terminated. The law requires that payment of benefits and health insurance coverage continue for terminated recipients until they have exhausted their appeals and that decisions by the Social Security Administration to terminate benefits are made only on the basis of “the weight of the evidence” in a particular recipient’s case.

The Voting Accessibility for the Elderly and Handicapped Act mandates that polling places be accessible or that ways be found to enable elderly and disabled people to exercise their right to vote. Advocates find that the act is difficult, if not impossible, to enforce.

1985 - The U.S. Supreme Court rules, in Burlington School Committee v. Department of Education, that schools must pay the expenses of disabled children enrolled in private programs during litigation under the Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975, if the courts rule such placement is needed to provide the child with an appropriate education in the least restrictive environment.

The U.S. Supreme Court rules, City of Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Center, that localities cannot use zoning laws to prohibit group homes for people with developmental disabilities from opening in a residential area sole because its residents are disabled.

1986 - The Air Carrier Access Act is passed, prohibiting airlines from refusing to serve people simply because they are disabled, and from charging them more for airfare than non-disabled travelers.

The National Council on the Handicapped issues Toward Independence, a report outlining the legal status of Americans with disabilities, documenting the existence of discriminating and citing the need for federal civil rights legislation (what will eventually be passed as the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990).

The Employment Opportunities for Disabled Americans Act is passed, allowing recipients of Supplemental Security Income and Social Security Disability Insurance to retain benefits, particularly medical coverage, even after they obtain work. The act is intended to remove the disincentives that keep disabled people unemployed.

The Protection and Advocacy for Mentally Ill Individuals Act is passed, setting up protection and advocacy agencies for people who are in-patients or residents of mental health facilities. Protection and advocacy for persons with mental illness (PAIMI) was included as a funded program for the organizations that had been assigned the PADD agencies in each state.

1987 - The US. Supreme Court, in School Board of Nassau County, Fla. v. Airline, outlines the rights of people with contagious disease under Title V of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. It establishes that people with infectious; diseases cannot be fired from their jobs “because of prejudiced attitude or ignorance of others.” This ruling is a landmark precedent for people with tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, and other infectious diseases or disabilities, and for people, such as individuals with cancer or epilepsy, who are discriminated against because others fear they may be contagious.

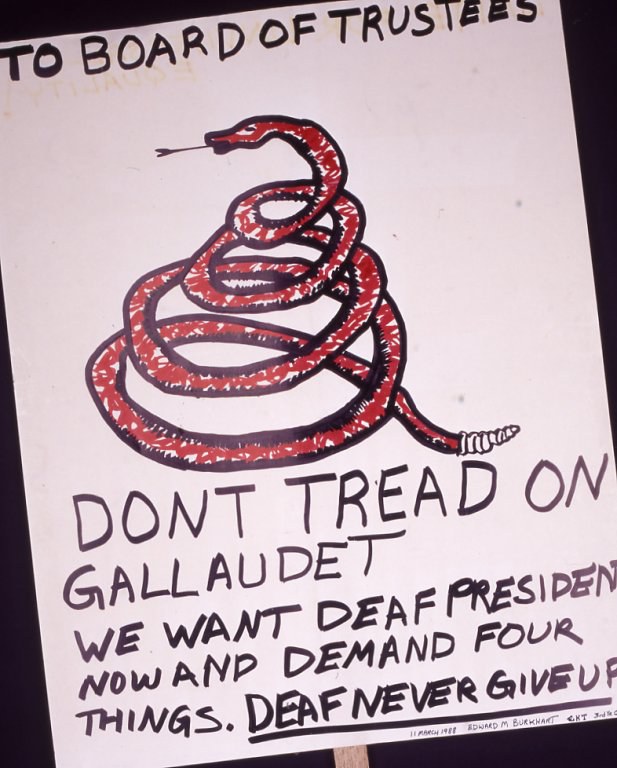

1988 - Students and alumni of Gallaudet University defied their board of trustees to force the hiring of a deaf person as president. Previously, the liberal arts school for deaf students, founded in 1864, had always selected a hearing president. Many felt the time had come for a deaf person to be appointed to this prominent position. Demonstrating students shut down the campus for a week before winning their demands. The "Deaf President Now" campaign strengthened the position of other activists then negotiating the Americans with Disabilities Act in Congress.

On March 13, 1988 the Gallaudet administration announces that I. King Jordan will be the university’s first deaf president.

The Technology-Related Assistance Act for Individuals with Disabilities (the “Tech Act” is passed, authorizing federal funding to state projects designed to facilitate access to assistive technology.

The Fair Housing Amendments Act adds people with disabilities to those groups protected by federal fair housing legislation, and it establishes minimum standards of an adaptability for newly constructed multiple-dwelling housing.

The National Council on the Handicapped issues On the Threshold of Independence and a first draft of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which is introduced into Congress by Rep. Tony Coelho and into the Senate by Sen. Lowell Weicker.

The Congressional Task Force on the Rights and Empowerment of Americans with Disabilities is created by Rep. Major R. Owens and co-chaired by Justine Dart Jr. and Elizabeth Boggs. The task force begins building grassroots; support for passage of the ADA. Justin Dart would later be sitting next to President George Bush when he signs the Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990. Justin was often seen on the front line of the disability rights struggle. He was a man of great means. He founded and was chief executive of Japan Tupperware Inc. His father, the late Justin Dart, was a California industrialist and close friend of President Reagan.

Congress overturns President Ronald Reagan’s veto of the Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987. The act undoes the Supreme Court decision in Grove City College v. Bell and other decisions limiting the scope of federal civil rights law, including Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973.

The U.S. Supreme Court, in Honig v. Doe, affirms the “stay put rule” established under the Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975, under which school authorities cannot expel or suspend or otherwise move disabled children from the setting agreed upon the child’s Individualized Education Program (IEP) without a due process hearing.

1989 - The federal appeals court, in ADAPT v. Skinner, rules that federal regulations requiring that transit authorities spend only 3 percent of their budgets on access are arbitrary and discriminatory.

The original version of the American with Disabilities Act, introduced into Congress the previous year, is redrafted and reintroduced. Disability organizations across the country advocate on its behalf with Patrisha Wright as “general” and Marilyn Golden, Liz Savage, Justin Dart Jr., and Elizabeth Boggs as principal coordinators or this effort.

The President’s Committee on Employment of the Handicapped is renamed the President’s Committee on Employment of People with Disabilities.

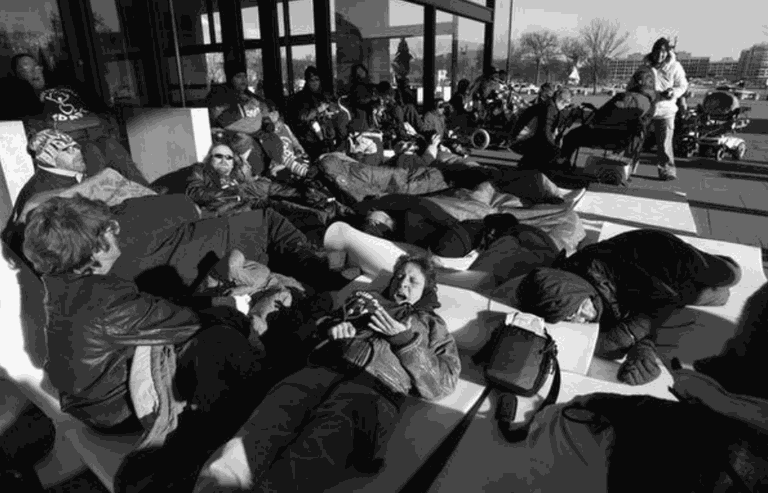

1990 - The Wheels of Justice campaign in Washington, D.C., organized by American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit (ADAPT), brings hundreds of disabled people to the nation’s capital in support of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADAPT) activists occupy the Capitol rotunda, and are arrested when they refuse to leave.

The Americans with Disabilities Act is signed into law by President George Bush on 26 July in a ceremony on the White House lawn witnessed by thousands of disability rights activists. The law is the most sweeping disability rights legislation in history, for the first time bringing full legal citizenship to Americans with disabilities. It mandates that local, state, and federal governments and programs be accessible, that businesses with more than 15 employees make “reasonable accommodations” for disabled workers, that public accommodations such as restaurants and stores make “reasonable modifications” to ensure access for disabled members of the public. The act also mandates access in public transportation, communication, and in other areas of public life.

With passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit (ADAPT) changes its focus to advocating for personal assistance services and changes its name to American Disabled for Attendant Programs Today.

The Education for All Handicapped Children Act is amended and renamed the Individuals with Disabilities; Education Act (IDEA).

1991 – The Kansas Mental Health Reform Act is signed into law by Governor Mike Hayden. This law sets up and formalizes a statewide network of community mental health centers, to ensure that those with mental health needs can be served in the community, helping to better avoid stays in state psychiatric hospitals.

Jerry’s Orphans stages its first annual picket of the Jerry Lewis Muscular Dystrophy Association Telethon.

The final federal appeals court ruling in Holland v. Sacramento City Unified School District affirms the right of disabled children to attend public school classes with non-disabled children. The ruling is a major victory in the ongoing effort to ensure enforcement of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

1995 - Justice for All is founded in Washington, D.C.

The U.S Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, in Helen L. v. Snider, rules that the continued publicly funded institutionalization of a disabled Pennsylvania woman in a nursing home, when not medically necessary, and where the state of Pennsylvania could offer her the option of home care, is a violation of her rights under the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. Disability rights advocates hail this ruling as a landmark decision regarding the rights of people in nursing homes to personal assistance services, allowing them to live at home.

1996 - Congress passes legislation eliminating more than 150,000 disabled children from the Social Security rolls, as well as individuals who are alcohol or drug dependent.

Kansas passes the Developmental Disabilities Reform Act, formalizing the structure to strengthen and better ensure that long-term care is provided in community-based settings instead of institutions.

Sandra Jensen, a member of People First, is denied a heart-lung transplant by the Stanford University School of Medicine because she has Down Syndrome. After pressure from disability rights activists, administrators there reverse their decision, and in January 1996, Jensen becomes the first person with Down Syndrome to receive a heart-lung transplant.

Not Dead Yet is formed by disabled advocates to oppose Jack Kevorkian and the proponents of assisted suicide for people with disabilities. The Supreme Court agrees to hear several right-to-die cases, and disability rights advocates redouble their efforts to prevent a resurgence of “euthanasia” and “mercy killing” as practiced by the Nazis against disabled people during World War II. Of particular concern are calls for the “rationing” of health care to people with severe disabilities and the imposition of “Do Not Resuscitate” (DNR) orders for disabled people in hospitals, schools, and nursing homes.

1997 - The IDEA reauthorization that took place in 1997 expanded the responsibilities for schools to involve and solicit input of parents , it increased the due process rights of parents related to disciplinary actions taken against children with disabilities, and it substantially strengthened the requirements for education in the least restrictive environment (LRE). “Appendix A” was designed to communicate the LRE means that it is presumed the general education classroom is the true least restrictive educational setting, and that auxiliary aids and services are to be provided that empower every student to remain in that “placement.” Today, if a school attempts to remove a student from the general education classroom to a setting that is 25% or more restrictive they must follow certain procedures involving the parent in the decision making, etc.

Topeka State Hospital is officially closed. However, the Hospital’s cemetery is a reminder of the thousands of individuals who resided in the facility during its more than 100 year history. The cemetery hosts the unmarked burial sites for more than 1100 residents who died during their stay. Fewer than ten plots have any kind of marker.

1998 - Bragdon v. Abbott: This case is important because the Court recognized HIV to be a disability under the ADA. The Court found that a person with HIV does have a disability because they are restricted in the major life activity of procreation.

1999 - Olmstead v. L.C. and E.W: This Supreme Court case that determined that forced institutionalization is discrimination. Olmstead requires that Medicaid services, e.g., long term care, must be provided in the most inclusive / integrated setting. In other words, people who are eligible for long term care can not be forced into nursing homes, group homes or other institutions. The state must provide community based options.

Murphy vs. UPS: This ADA employment case was a setback for people with disabilities protections from discrimination. Murphy was terminated from his position because of hypertension. The court found that that Mr. Murphy was not “disabled” under the definition in the ADA because his condition was controlled by medication. Therefore his claim of discrimination on the basis of disability was denied. Essentially, the court re-defined disability to not only include the persons impairment, but that the impairment must be evaluated in its mitigated state. In other words, if you have a disability which by itself falls into the ADA’s definition of disability, but you use technology, medication, or some other mitigating treatment that eliminates the affect of the disability on the person’s ability to function, you are no longer considered an individual with a disability under the law.

Activists who oppose euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide created this pin in 1999. T4, short for the address Tiergarten 4, was a Nazi work group of psychiatrists and physicians. During World War II, they were in charge of the killing of more than 100,000 people with disabilities. Life with a disability often has been perceived as not worth living. As recently as 1983, fifteen states still had laws that required the sterilization of people with disabilities.

2001 – UAB vs. Garnett: this Supreme Court case resulted in an expansion of state’s rights of Sovereign Immunity under the 14th Amendment to the Constitution. The Court said that a state can not be sued by it’s employees for any action that it takes. Thos case severely restricts state employees due process rights under the ADA and other civil rights laws.

Help America Vote Act: A response the problems encountered in Florida during the 2000 General Election, HAVA again ensures people with disabilities equal access to the election process. Lack of understanding of the laws requiring access is widespread not only in Kansas, but also around the country. Here is just one example of how voters with disabilities have been relegated to a separate and unequal system.

Pittsburgh (Pennsylvania) Post-Gazette

Access to polls is problematic for disabled voters

Too many find that exercising their right is all but impossible, despite

1984 law

Wednesday, April 28, 2004

By Gary Rotstein

Lois O'Donnell got the chance to vote yesterday without getting off her electric scooter and entering her Carnegie polling place, once she explained to precinct workers that she was unable to get up and down the church steps.

To O'Donnell, 65, it was a case of democracy being served but in discriminatory fashion. She had to fill out a paper ballot in public, when able-bodied individuals could vote privately behind curtains.

To Allegheny County Elections Director Mark Wolosik, O'Donnell's vote was a mistake. He said disabled individuals with inaccessible voting sites are supposed to register at least a week in advance for what's known as an "alternative" ballot, which O'Donnell did not do.

2002 – Justin Dart, Jr. passes away. The disability community loses an amazing advocate.

2004 – Kansas passes a law to require that all polling places be fully accessible to people with disabilities. The previous law, passed in the 1970s, only said that polling places had to be accessible in the “foreseeable future.” The Disability Rights Center of Kansas, and other disability advocates, successfully argued that the foreseeable future had passed, and that Kansas had a duty to ensure that its polling places were fully accessible. The HAVA Act was also used as a catalyst to obtain passage of this provision in Kansas.

MiCASSA, the Medicaid Community Attendant Services and Supports Act in Introduced. MiCASSA is A COMMUNITY-BASED ALTERNATIVE TO NURSING HOMES AND INSTITUTIONS FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES.

For decades, people with disabilities, both old and young, have wanted alternatives to nursing homes and other institutions when they need long-term services. Our long term care system has a heavy institutional bias. Every state that receives Medicaid MUST provide nursing home services, but community based services are optional. Seventy five percent of Medicaid long term care dollars pay for institutional services, while the remaining 25% must cover all the community based waivers, optional programs, etc.

Families are in crisis. When support services are needed there are no real choices in the community. Whether a child is born with a disability, an adult has a traumatic injury or a person becomes disabled through the aging process, they overwhelmingly wan t their attendant services provided in their own homes, not nursing homes or other large institutions. People with disabilities and their families will no longer tolerate being forced into selecting institutions. It's time for Real Choice.

ADAPT has drafted a bill which will fundamentally change our long term care system and institutional bias that now exists. Instead people with disabilities and their families will be able to choose where and how they receive services.

MiCASSA, the Medicaid Community Attendant Services and Supports Act, is that alternative! Instead of making a new entitlement, MiCASSA makes the existing entitlement more flexible.

MiCASSA establishes a national program of community-based attendant services and supports for people with disabilities, regardless of age or disability. This bill would allow the dollars to follow the person, and allow eligible individuals, or their representatives, to choose where they would receive services and supports. Any individual who is entitled to nursing home or other institutional services will now have the choice where and how these services are provided. The two million Americans currently residing in nursing homes and other institutions would finally have a choice.

Though MiCASSA was not enacted, it helped change the debate on community based services and supports for people with disabilities.

ADAPT met with the US Department of Health and Human Services at their Washington D.C. offices in March 2004.

ADAPT continues to be a progressive conscience of the Disability Rights movement.

2006 – Congress adopts the “Money Follows the Person” legislation, which takes the funding sections of MiCASSA and provides incentives for states to provide home and community options to expensive institutions.

2008 – The American’s with Disabilities “Restoration” Act is signed into law, overturning activist conservative judges who systematically watered down or thwarted the original intent of the ADA. The following is a description from NCIL (National Council on Independent Living) about why the ADA Restoration Act was so important:

“Unfortunately, since 1999, the courts have dramatically scaled back the ADA definition to the point where it bears little resemblance to the robust civil rights law that Congress passed in 1990. In a series of Supreme Court cases, the Court decided that the use of medication, prosthetics, hearing aids, auxiliary devices, etc. must be considered when a court is determining if someone is covered under the law. That means that people with all kinds of disabilities who enjoy greater independence (including the ability to work) on account of medication, hearing aids, specific diets, prosthetics, etc., are often no longer covered under the ADA because the courts view their limitations as no longer substantial “enough.” Courts have even denied ADA protection to those whose employers have freely admitted that they terminated the individuals because of their disabilities!

The ADA was meant to be just like other civil rights laws that address employment discrimination – when someone experiences discrimination because of disability, the sole focus of the legal case should be on whether the actions of the employer were unlawful. However, the Courts have created an extra hoop for people with disabilities to challenge an employer’s actions. First, people with disabilities must “prove” their disability by providing highly personal and often wholly irrelevant information about their lives. Only if they have satisfied this difficult standard are they then permitted to present the facts of discrimination they encountered and increasingly, fewer and fewer people are able to get to that point.

Instead of following Congress’s clear intention that the definition of “disability” in the ADA be interpreted broadly, the Supreme Court decided to ignore Congressional intent and directed that the definition of disability needed to be interpreted narrowly. As a result, there have been hundreds of court cases with bizarre and devastating outcomes with the courts siding with the employer rather than individuals who faced discrimination more than 90% of the time. People with epilepsy, muscular dystrophy, multiple sclerosis, diabetes, cancer, HIV, intellectual disabilities (formerly known as “mental retardation”), hearing loss, major depression, PTSD, bipolar disorder, and many other disabilities are consistently being told they are not “disabled enough” and therefore not covered by the ADA.

By watering down civil rights protections for people with disabilities, the courts have created an unacceptable U-turn in the progress people with disabilities have made to date and have made it legal for an employer to say “You are not welcome here” to people with disabilities who have skills and who want to work.”

2010 – The most substantial health insurance reform in the history of our nation is signed into law by President Barack Obama. Two long-term care provisions are contained in this far larger bill that have a particularly important impact on people with disabilities. The first is the “community first choice option,” which ends the money follows the person initiative to 2016 and provides additional options to encourage states to stop the institutional bias against home and community based services.

The second long-term care provision contained in the larger health insurance reform bill is the CLASS Act (Community Living Assistance Services and Supports Act), which creates a national, voluntary long-term care disability insurance program through payroll deductions which would provide benefits based on the significance of the disability to purchase long-term care services and supports. This is an idea whose time has come. The CLASS Act provision provides long-term care services through this voluntary insurance program. So, how does one currently qualify for long-term care services and supports for a disability? Typically you must either purchase private long-term care insurance (which is cost prohibitive) or be forced into poverty in order to qualify for Medicaid and Social Security to obtain the long-term care services and supports you need to accommodate your disability needs. Kansas has the 35th lowest, or worst, income eligibility requirements for Medicaid. Many Kansans with disabilities are living on far, far less than $700 a month just to qualify for these critical services through Medicaid.

The current system forces people into poverty and creates dependence. The CLASS Act creates a nationwide optional long-term care insurance benefit to break that cycle by creating an opportunity for independence.

The cost of providing long-term care services and supports are projected to more than double by 2040 due to the aging of Americans, including the baby boomers.

Medicaid should not have to continue to pay the majority of these costs because:

• People should not be required to become very poor, give up their assets, and have severe functional limitations in order to access services and supports, and

• The growing costs of long-term services and supports will put increasing strain on the Medicaid system.

The CLASS Act takes a step in the right direction by putting people more in charge of their long-term care needs.

AMERICA AND KANSAS HAVE A LONG AND CRUEL HISTORY OF DISCRIMINATION AGAINST PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES.

To understand the disability rights movement and the positive recent developments to protect the rights of people with disabilities, you must appreciate the history of discrimination and isolation thrust upon them. For much of our nation’s history, Americans who happen to have disabilities were considered as people without any real value to society, a drain on the government’s resources, and a population without any real political or economic power. Some in our society still feel this way today.

Discrimination is the making of distinctions in the way a person or class of persons is treated based on a particular characteristic or set of characteristics of that individual(s). In this case that characteristic is disability. Examples of discriminatory acts range from a one-inch step into a building, to forced institutionalization, and to the most heinous examples of abuse and neglect. The history of discrimination, forced institutionalization, forced sterilization, denial of education, being hidden away from society, etc., has been well documented by Congress and by the Courts.

Below are excerpts from a court case, Tennessee v. Lane, U.S. Supreme Court brief, November 12, 2003. The following are quotes from the court briefs. Reading these passages provides an excellent summary of the historic discrimination faced by people with disabilities in our nation.

“After decades of study, Congress determined that persons with disabilities had suffered from a virulent history of official governmental discrimination, isolation, and segregation. Congress found, moreover, that such discrimination and segregation, like race and gender discrimination, have repercussions that have persisted over the years and that continue to be manifested in decision making by state and local officials across the span of governmental operations. That official discrimination results not just in the denial of the equal protection of the laws and equal access to governmental benefits, but also in the deprivation of fundamental rights, such as the rights of access to the courts, to vote, to substantive and procedural due process, to petition government officials, and to other protections of the First, Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, and Eighth Amendments.”

While referring to the Americans with Disabilities act of 1990 it states, “In Title II, Congress formulated a statute that, much like federal laws combating racial and gender discrimination, is carefully designed to root out present instances of unconstitutional discrimination, to undo the effects of past discrimination, and to prevent future unconstitutional treatment by prohibiting discrimination and promoting integration where reasonable. . . . The statute is thus carefully tailored to prohibit state conduct that presents a substantial risk of violating the Constitution or that unreasonably perpetuates the exclusionary effects of prior unconstitutional treatment and exclusion.”

“Persons with disabilities reported "denials of educational opportunities, lack of access to public buildings and public bathrooms, [and] the absence of accessible transportation.” Congress also learned of an “alarming rate of poverty,” a dramatic educational gap, and a life of social “isolat[ion]” for persons with disabilities.’

“Twenty percent of persons with disabilities--more than twice the percentage for the general population--lived below the poverty line, and 15% of disabled persons had incomes of $15,000 or less. Threshold 13-14. Forty percent of persons with disabilities--triple the rate for the general population--did not finish high school. Only 29% of persons with disabilities had some college education, compared with 48% for the general population. Two-thirds of all working-age persons with disabilities were unemployed; only one in four worked full-time. Two- thirds of persons with disabilities had not attended a movie or sporting event in the past year; three-fourths had not seen live theater or music performances; persons with disabilities were three times more likely not to eat in restaurants; and 13% of persons with disabilities never went to grocery stores.”

Historic Discrimination: The “propriety of any legislation 'must be judged with reference to the historical experience ... it reflects.” Florida Prepaid Postsecondary Educ. Expense Bd. v. College Sav. Bank, 527 U.S. 627, 640 (1999) (quoting Flores, 521 U.S. at 525). While petitioner and its seven amici States ignore it, Congress and this Court have long acknowledged the Nation's “history of unfair and often grotesque mistreatment” of persons with disabilities. Cleburne, 473 U.S. at 454 (Stevens, J., concurring); see also Olmstead v. L.C., 527 U.S. 581, 608 (1999) (Kennedy, J., concurring) (“[O]f course, persons with mental disabilities have been subject to historic mistreatment, indifference, and hostility.”); Cleburne, 473 U.S. at 446 (“Doubtless, there have been and there will continue to be instances of discrimination against the retarded that are in fact invidious.”); Alexander v. Choate, 469 U.S. 287, 295 n.12 (1985) (“well- cataloged instances of invidious discrimination against the handicapped do exist”).

“[T]orture, imprisonment, and execution of handicapped people throughout history are not uncommon.” United States Civil Rights Comm'n, Accommodating the Spectrum of Individual Abilities 18 n.5 (1983) (Spectrum). More often, “societal practices of isolation and segregation have been the rule.” From the 1920s to the 1960s, the eugenics movement labeled persons with mental and physical disabilities as “sub-human creatures” and “waste products” responsible for poverty and crime. Every single State, by law, provided for the segregation of persons with mental disabilities and, frequently, epilepsy, and excluded them from public schools and other state services and privileges of citizenship. States also fueled the fear and isolation of persons with disabilities by requiring public officials and parents to report and segregate into institutions the “feebleminded.”

“Almost every State accompanied forced segregation with compulsory sterilization and prohibitions on marriage. See Buck v. Bell, 274 U.S. 200, 207 (1927) ("It is better for all the world, if . . . society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind. . . . Three generations of imbeciles are enough."); 3 Leg. Hist. 2242; M. Burgdorf & R. Burgdorf, A History of Unequal Treatment (Unequal Treatment), 15 Santa Clara Lawyer 855, 887-888 (1975). Children with mental disabilities “were excluded completely from any form of public education.” Board of Educ. v. Rowley, 458 U.S. 176, 191 (1982). Numerous States also restricted the rights of the physically disabled to enter into contracts, Spectrum 40, while a number of large cities enacted “ugly laws,” which prohibited the physically disabled from appearing in public. Chicago's law provided:

“No person who is diseased, maimed, mutilated or in any way deformed so as to be an unsightly or disgusting object or improper person to be allowed in or on the public ways or other public places in this city, shall therein or thereon expose himself to public view, under a penalty of not less than one dollar nor more than fifty dollars for each offense. Unequal Treatment 863 (quoting ordinance). Such laws were enforced as recently as 1974.”

“See also State v. Board of Educ., 172 N.W. 153, 153 (Wis. 1919) (approving exclusion of a boy with cerebral palsy from public school because he “produces a depressing and nauseating effect upon the teachers and school children.”) (noted at 2 Leg. Hist. 2243); see generally T. Cook, The Americans with Disabilities Act: The Move to Integration, 64 Temple L. Rev. 393, 399-407 (1991).”

Enduring Unconstitutional Treatment: “Prejudice, once let loose, is not easily cabined.” Cleburne, 473 U.S. at 464 (Marshall, J., concurring); see Hibbs, 123 S. Ct. at 1979 (noting the “persistence” of gender discrimination and the “firmly rooted” stereotypes that accompany it). Indeed, Congress found that “our society is still infected by the ancient, now almost subconscious assumption that people with disabilities are less than fully human and therefore are not fully eligible for the opportunities, services, and support systems which are available to other people as a matter of right,” and “[t]he result is massive, society-wide discrimination.” S. Rep. No. 116, supra, at 8-9.

Another section reads, “That is because a concerted process of changing discriminatory laws, policies, practices, and stereotypical conceptions and prejudices did not even begin until the 1970s and 1980s. Cf. Hibbs, 123 S. Ct. at 1978. Even then, “out-dated statutes [were] still on the books, and irrational fears or ignorance, traceable to the prolonged social and cultural isolation” of those with disabilities “continue to stymie recognition of the[ir] dignity and individuality.” Cleburne, 473 U.S. at 467 (Marshall, J., concurring) (emphasis added). The involuntary sterilization of the disabled is not distant history; it continued into the 1970s, and occasionally even into the 1980s-- well within the lifetime of many current governmental decision makers. P. Reilly, The Surgical Solution 2, 148 (1991); Look Back at Oregon's History of Sterilizing Residents of State Institutions (National Pub. Radio broadcast Dec. 2, 2002). As recently as 1983, fifteen States continued to have compulsory sterilization laws on the books. Spectrum 37; see Stump v. Sparkman, 435 U.S. 349, 351 (1978) (state judge ordered the sterilization of a “somewhat retarded” 15-year-old girl); Reilly, supra, at 148-160; contrast Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535, 541 (1942) (strict scrutiny governs sterilization classifications). Until the late 1970s, “peonage was a common practice in [Oregon] institutions.” Governor J. Kitzhaber, Proclamation of Human Rights Day, and Apology for Oregon's Forced Sterilization of Institutionalized Persons, Speech at Salem, Or. (Dec. 2, 2002). As of 1979, “most States still categorically disqualified ‘idiots’ from voting, without regard to individual capacity and with discretion to exclude left in the hands of low-level election officials." Cleburne, 473 U.S. at 464 (Marshall, J., concurring).

Congress learned that irrational prejudices, fears, and animus still operate to deny persons with disabilities an equal opportunity for public education. As recently as 1975, approximately 1 million disabled students were “excluded entirely from the public school system.” 42 U.S.C. 1400(c)(2)(C). A quadriplegic woman with cerebral palsy and a high intellect was branded “retarded” by educators, denied placement in a regular school setting, and placed with emotionally disturbed children, where she was told she was “not college material.” VT 1635. Other school districts also simply labeled as mentally retarded a blind child and a child with cerebral palsy. NB 1031; AK 38 (child with cerebral palsy subsequently obtained a Masters Degree). “When I was 5,” another witness testified, “my mother proudly pushed my wheelchair to our local public school, where I was promptly refused admission because the principal ruled that I was a fire hazard.”

See also California. Attorney General, Commission on Disability: Final Report 17, 81 (Dec. 1989) (Cal. Report) (“A bright child with cerebral palsy is assigned to a class with mentally retarded and other developmentally disabled children solely because of her physical disability”; in one town, all children with disabilities are grouped into a single classroom regardless of individual ability.); 136 Cong. Rec. 10,913 (1990) (Rep. McDermott) (school board excluded Ryan White, who had AIDS, not because the board “thought Ryan would infect the others” but because “some parents were afraid he would”); NY 1123 (three elementary schools locked mentally disabled children in a box for punishment); Education for All Handicapped Children, 1975-1974: Hearings Before the Subcomm. on the Handicapped of the Senate Comm. on Labor & Pub. Welfare, 93d Cong., 1st Sess., Pt. 2, at 793 (1973) (Christine Griffith) (first-grade student “was spanked every day” because her deafness prevented her from following instructions); id., Pt. 1, at 400 (Mrs. R. Walbridge) (student with spina bifida barred from the school library “because her braces and crutches made too much noise”); id. at 384; 2 Leg. Hist. 989; Spectrum 28, 29; UT 1556; PA 1432; NM 1090; OR 1375; AL 32; SD 1481; MO 1014; NC 1144; Garrett, 531 U.S. at 391-424 (Breyer, J., dissenting).

There is a long and unfortunate history of people with disabilities being denied access to government services and programs. A few examples: A paraplegic Vietnam veteran was forbidden to use a public pool; the park commissioner explained that “[i]t's not my fault you went to Vietnam and got crippled.” 3 Leg. Hist. 1872 (Peter Addesso); see also id. at 1995 (Rev. Scott Allen) (woman with AIDS and her children denied entry to a public swimming pool); 2 Leg. Hist. 1100, 1078, 1116; WS 1752 (deaf child denied swimming lessons); NC 1156 (mentally retarded child not allowed in pool); CA 166; MS 855; May 1989 Hearings 76 (Ill. Att'y Gen. Hartigan) (visually impaired children with guide dogs “cannot participate in park district programs when the park has a ‘no dogs’ rule”); NC 1155; PA 1391 (limiting library cards for “those having physical as well as mental disabilities”); CA 216 (wheelchair users not allowed in homeless shelter); CA 223 (same); DE 322 (same for mentally ill); KS 713 (discrimination in state job training program); IL 533 (female disability workshop participants advised to get sterilized); IA 664; AK 72, 145; OH 1218; AZ 116; AZ 127; HI 456; ID 541; see generally Spectrum App. A (identifying 20 broad categories of state-provided or supported services and programs in which discrimination against persons with disabilities arises).

The examples above are used to provide context to the history of discrimination against people with disabilities because it provides a snapshot of just how pervasive the abuse, neglect, segregation, isolation, institutionalization and other severe forms of discrimination really are. In fact, actions and attitudes of discrimination against people with disabilities were, and are, so pervasive that after several years of hearings and study, even Congress figured out that something needed to change.

CREATION OF THE PROTECTION & ADVOCACY (P&A) SYSTEM

The protection and advocacy system was founded in 1975 because of the sudden public acknowledgment of the horrific abuses that people with developmental disabilities were experiencing in institutions all around the country. Unfortunately by the mid 1970s thousands upon thousands of individuals with disabilities had been forced to live in institutions and as a result had been brutally abused, tortured and denied any chance at the life that other Americans enjoyed. In Kansas, the Disability Rights Center of Kansas is the Protection and Advocacy System, having been founded in 1977.

People with a wide range of disabilities were, and still are institutionalized. People were referred to as the “feeble minded, epileptics, Mongolian idiots, imbeciles, and insane.” Numerous public policies and practices of publicly mandated, publicly funded and publicly accepted discrimination and abuse were instituted. Today, the institutions look different in size, color, location, furnishings and appearance, but make no mistake, an institution is an institution is an institution. Regardless of how well meaning the intent, any living situation where the “owner,” service provider, administration or other systems or persons control your lifestyle, your room mates, your money, your meals, your recreation and your movements, (and on and on), is an institution. Institutions by their very nature deny, withhold, violate and abuse the rights of the people that live there.

In response to the historic discrimination against people with disabilities, the Protection and Advocacy (P&As) System. Every state and most US Territories have a designated protection and advocacy system (again, in Kansas this is the Disability Rights Center). P&As provide legally-based advocacy, including free advocacy and legal services, to people with disabilities in order to protect, enforce and enhance their rights under the law. P&As also have special powers under federal law to investigate abuse and neglect, along with the corresponding authority to hold abusers accountable through civil actions.

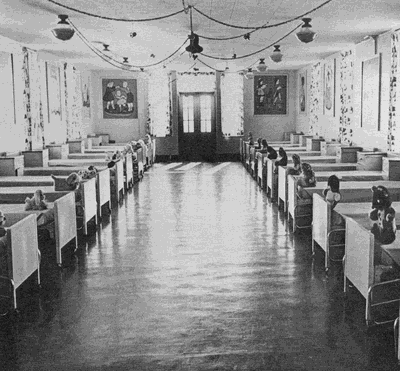

Pictures from the book Christmas in Purgatory

“During the eighteenth century the plight of the mentally ill was shocking almost everywhere in Europe. ...flighty, troublesome or dangerous patients were restrained and kept in a small room or stall in a private house, in ‘lunatic boxes,’ in cages or in other places of confinement that seemed appropriate for isolating them and rendering them harmless...as a result of poor supervision, many committed suicide, perished through accidents or created serious disturbances. The tense and exasperating environment thus created and encouraged the establishment of the strictest preventative measures.” - Emil Kraepelin (Christmas In Purgatory)

Eugenics: the pseudo-science that was a tool for oppression and systematic abuse against people with disabilities

Among the most heinous of the systematic abuses of persons with disabilities was the eugenics movement.

In 1883 Sir Francis Galton in England coined the term eugenics to describe his pseudo-science of “improving the stock” of humanity. The eugenics movement, taken up by Americans, leads to passage in the United States of laws to prevent people with disabilities from moving to this country, marrying, or having children. In many instances, it leads to the institutionalization and forced sterilization of disabled people, including children.

THE EUGENIC TREE. This emblem, showing the far-flung roots of eugenics, was part of a certificate awarded to ‘meritorious exhibits’ at the Second International Congress of Eugenics, held in 1921 at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. (Image courtesy of the American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, USA.)

In his article “Never Again” (February 2000), Ward Harkavy writes:

“Eugenicists believed that bone structure held clues about character traits. A century ago, scientists from the top universities in America began to study people's pedigrees in the hopes of creating ‘perfect’ children. Instead, they spawned a monster: the pseudoscience of eugenics. We bury memories of those days under a mountain of shame; rarely does the full scope of our flirtation with race science come to light.”

But now more than 1200 images from the heyday of eugenics are about to be opened to wide public view, under a program funded by the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on Long Island.

The Image Archive on the American Eugenics Movement, vector.cshl.org/eugenics/http://vector.cshl.org/eugenics/ , pieced together by a staff led by David Micklos of the lab's DNA Learning Center, contains explosive material on such topics as “race mixing” and “Mongolian idiocy.” Well-written essays accompany the images and put the times in perspective.

It's more than coincidence that the Cold Spring Harbor Lab hosts this project. It is, after all, home of the Human Genome Project to map DNA. A fairly straight line connects this project to the early eugenics movement, although the scientists of yesteryear took gene research down a darker road. Believing that single genes could determine whether someone would be ‘inferior,’ they hoped to build a better human by deciding who should or shouldn't make babies. Minority groups were most often the target of this plan.

In 1910, the Eugenics Record Office was set up at Cold Spring Harbor, making the lab the center of what became an international movement. In the United States, the results ranged from ‘Fitter Families’ contests, aimed at encouraging people of ‘good stock’ to breed, to laws restricting immigration of non-WASPs and ordering sterilization of the ‘feebleminded.’

Arguing for limiting immigration from southern and eastern Europe, Harry Laughlin, head of the ERO, told Congress in 1920, "We in this country have been so imbued with the idea of democracy or the equality of all men that we have left out of consideration the matter of blood or natural inborn hereditary mental and moral differences." Adolf Hitler, of course, took the same logic to pathological conclusions, using eugenics as a rationale for genocide.

Micklos, the site's editor, doesn't mince words about the American involvement in eugenics. In one essay, he describes the ERO's journal Eugenical News as the “dominant mouthpiece for the racist and anti-immigration agenda of eugenics research.”

The digital archive serves as a reminder that crackpot science isn't just the domain of Nazis and ignorant racists. Among the leaders of the American eugenics movement were Stanford president David Starr Jordan, Luther Burbank, and Alexander Graham Bell. Charles Darwin's son headed the Eugenics Society in England. The ERO itself was endowed by a grant from the widow of railroad magnate E.H. Harriman, and such population-control progressives as Margaret Sanger also believed in the cause.

Making the history public: apologies and promises of a better tomorrow

Just a few years ago, the Governor of Virginia publicly apologized for that state’s history of institutionalization, and more directly the forced sterilization of thousands of Virginians. Below is a Kansas City star article that provides the Missouri connection to the Eugenics movement.

The 1927 U.S. Supreme Court, in Buck v. Bell, ruled that the forced sterilization of people with disabilities is not a violation of their constitutional rights. The decision removed the last restraints for eugenists; advocating that people with disabilities be prohibited from having children. By the 1970s, some 60,000 disabled people were sterilized without consent.

“We have seen more than once that the public welfare may call upon the best citizens for their lives. It would be strange if it could not call upon those who already sap the strength of the State for these lesser sacrifices, often not felt to be such by those concerned, in order to prevent our being swamped with incompetence. It is better for all the world if, instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind. . . . Three generations of imbeciles are enough. [p*208]” Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, United States Supreme Court.

In his Kansas City Star article on the eugenics movement in the Midwest, Michael L. Wehmeyer states the following: The effort to sterilize the unfit in Kansas began in 1894 with F. Hoyt Pilcher, then superintendent of Winfield's Kansas State Asylum for Idiotic and Imbecile Youth.

By 1895, Pilcher had developed a reputation as a trailblazer. The

Winfield Courier reported: “The unsexing of one hundred and fifty of these inmates—male and female—was an innovation that received the endorsement of the entire medical profession of the world, and the plaudits of right thinking people everywhere.” On March 14, 1913, Kansas, well after Pilcher's reign, passed a law stating that forced sterilization was acceptable if “the mental or physical condition of any inmate would be improved . . . or that procreation by such inmates would be likely to result in defective or feeble-minded children.”

On October 6, 1928, the Supreme Court in Kansas held that a later version of the Kansas sterilization law (passed March 13, 1917) was constitutional. Landman (1932) observed that “The Buck v. Bell decision mandated May 2, 1927 has definitely altered the judicial opinion of this country in favor of this kind of legislation”. (Eugenics and Sterilization in the Heartland, 2002)

By the mid 1970s nearly 3,000 Kansans had undergone forced sterilization in the state run “hospitals” for persons with mental illness and developmental disabilities. Kansas hosted the third most active eugenics program in the country just behind Virginia and California. For its population, Kansas probably subjected the highest percentage of its population to this crime. The State of Kansas continues to operate 4 large institutions for citizens with disabilities located in Larned, Ossawtomie, Parsons and Topeka.

“Cast upon this globe without physical strength or innate ideas, incapable in himself of obeying the fundamental laws of this nature which call him to the supreme place in the universe, it is only in the heart of society that man can attain the pre-eminent position which is his natural destiny. Without the aid of civilization he would be one of the feeblest and least intelligent of animals...”

- Jean-Marc-Gaspard Itard

NEVER FORGET - NEVER AGAIN

Never Forget and Never Again are two slogans that have been used to help us remember what was, and what should be. The reader must remember that this is only a brief accounting of the long and varied history of the discrimination and abuse of people who have disabilities and the many attempts to make things better. The history serves to remind us that the job of ensuring justice and equality is not completed. DRC’s very purpose is to do everything in its power to make sure that never again will Kansans with disabilities experience the discrimination, abuse, torture, segregation and denial of the most basic of human and civil rights that other Americans enjoy.

I think that she would agree.

Note: Many of the facts and information printed in this document came from various sources. Many of the information came from the Bancroft Library, but some have unknown authors. Every attempt has been made to identify the publication and author where possible.

.png)